Some versions of the Cinderella story are full of gore and crime and punishment; others focus on sweet revenge. Some really play up magical and pagan elements, while others aim to serve as a kind of fantastical lesson in the redemptive powers of Christian virtues such as equanimity and kindness, especially for poor girls born into tough situations.

Kent Stowell’s 1994 remake for Pacific Northwest Ballet, which runs through February 8 at McCall Hall, leans into the story’s dreamier and more romantic/Romantic corners while still retaining the fun and freaky elements that make it feel like a fairy tail. The resulting magical romance gives Seattle audiences a chance to dip into an eighteenth-century dream, where we can marvel at designer Martin Pakledinaz’s richly textured costumes, hoot and holler at the company’s technical prowess, and witness the considerable acting chops of its principals.

Speaking of principals: I feel as if I’m seeing Leta Biasucci kick off opening night in lead roles more often, and I believe we’re all better for it. Though she has played leads on plenty of other nights, more often I’ve seen her on opening nights in supporting or comedic roles, showing off her advanced technical skills. Her timing and musicality are impeccable, her footwork is intricate, and she glides across the stage with the power and grace of an artist with nothing to prove, only something to say.

In the titular role, she convincingly transforms Cinderella from a sweet and humble castaway into a confident and beaming dream bride, carrying herself with a generosity of spirit you can see from the cheap seats. She exudes pathos and understanding when navigating her relationship with her father, who loves her but seems powerless to stop the cruelty of Cinderella’s stepmother and stepsisters. We believe her when she extends her hand to help her fairy godmother—disguised as an old homeless woman—warm up by the fire, and we swoon with her as she swoons for the prince. (Though I somewhat dismissively mentioned the virtues of equanimity and kindness in my introduction, those traits unfortunately run in short supply among many of us these days. Seeing Biasucci’s Cinderella model them so exquisitely felt like a breath of fresh air.)

But anyway, speaking of the Prince: I don’t know what Lucien Postlewaite does to maintain his vigor, but whatever it is, it’s working. On Friday night, he played the familiar role of the regal suitor with characteristic charm and gravitas. He hits all the prim and proper notes just so, but he also make big lifts look effortless — at one point he lifted Biasucci into the air and spun her around like a pizza without (apparently) breaking a sweat.

Corps de ballet member Melisa Guilliams offered up an elegant, grounded turn as the Godmother, with light beams practically emanating from her very being the whole time. What a dream.

Speaking of dreams: four fairies who embody the seasons dance for Cinderella in a couple of extended dream sequences, bestowing upon her magical powers. Standouts here included Yuki Takahashi as Spring, who floated across the stage like a petal, and Madison Rayn Abeo as winter, who carried herself with the season’s great power and austerity without coming off as frigid.

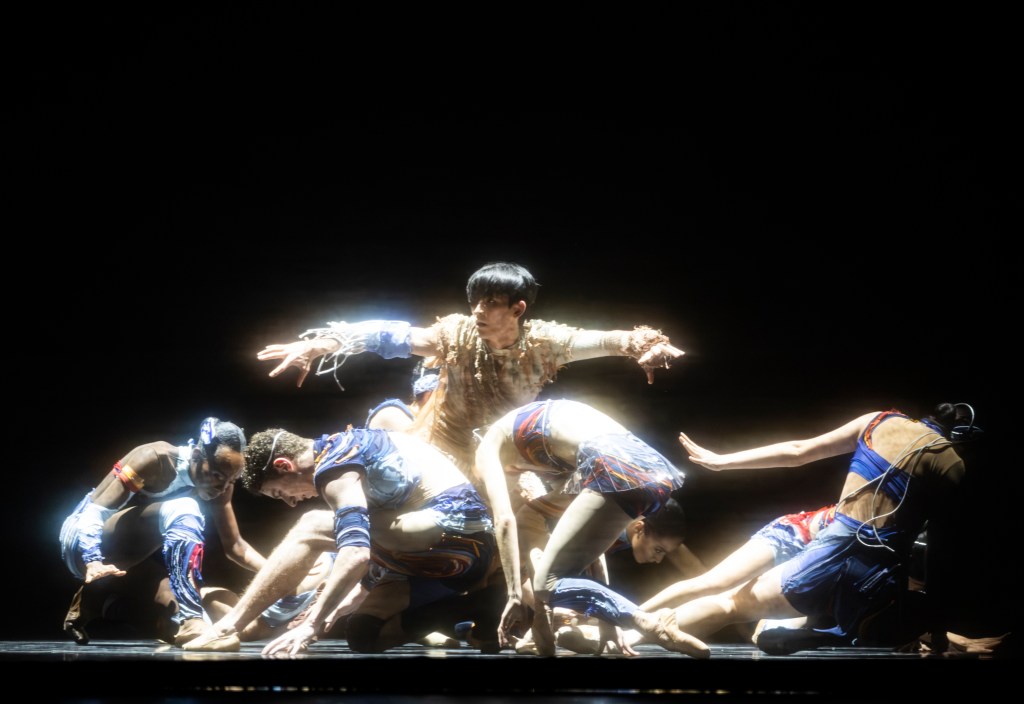

Though you’d think the best duet would go to Biasucci and Postlewaite’s romantic closing pas de deux, on Friday night, at least, it belonged to soloists Takahashi and Mark Cuddihee, who danced their roles as Columbine and Harlequin, respectively, with verve, humor and acrobatic panache. A special shout out goes to Corps member Zsilas Michael Hughes, whose role as a leggy flame demon dubbed “Evil Sprite” was so dynamic and arresting that it felt like a dream within a dream.

And finally, MVP of the night goes to Kuu Sakuragi, who played the Jester. The heart smiled when he leapt onstage, a dynamo in cap and bells. He jumps six feet in the air like it’s nothing, and his leg extensions were just crazy—nothing less than astonishing. It’s great to see him explore his comedic range, filling the proverbial pointe shoes of former PNB dancer and current PNB Rehearsal Director Ezra Thomson, who similarly employed his technical mastery for our comedic benefit.

All told, apart from the aggressively mauve color pallet of the scenic design, this old story of dreaming a little dream until it really does come true was a welcome escape from our particularly ugly political environment. Go see it for a nice rest and recharge, and for the sheer amazement of watching these dancers do their thing.