Anybody else feeling kinda weird about large portions of the world talking to a robot at their job all day, reaching for robot-curated content as an escape, and then trying to touch grass or reconnect with real living things but feeling like you can’t quite find life’s socket, as it were? Plus also feeling a little mopey because it’s dark a lot now? Well then, Pacific Northwest Ballet has just the program for you.

Like your most toxic, codependent friend, PNB’s In the Upper Room poisons you with its own loneliness and alienation, and then, just as you begin to fall into the void, it wrenches you from your doldrums with fun costumes and lots of aerobic exercise.

The program’s trio of ballets, which runs at McCaw Hall through Nov 16, includes a timely world premiere from PNB dancer-choreographers Amanda Morgan and Christopher D’Ariano called AfterTime, Dani Rowe’s heartbreaking/breathtaking The Window, and Twyla Tharp’s breathless In the Upper Room, a mid-1980s romp supercharged by Philip Glass’s manic minimalism. If the first two-thirds of this program make you feel like you want to to slink back to your apartment for a spliff and a 45-minute short-form video binge, the last third will make you want to swing dance on the moon.

Morgan and D’Ariano’s AfterTime presents a multimedia ballet featuring otherworldly costuming from Janelle Abbott, dazzling light work from Reed Nakayama, transportive film and projection design from Henry Wurtz, propulsive (and cleverly arranged) music from Fiona Stocks-Lyon and Thomas Nickell, and engrossing postmodern aesthetics with a big ol’ modernist heart beating at its center that nevertheless speaks to our increasingly post-human contemporary moment. (Haha sorry.)

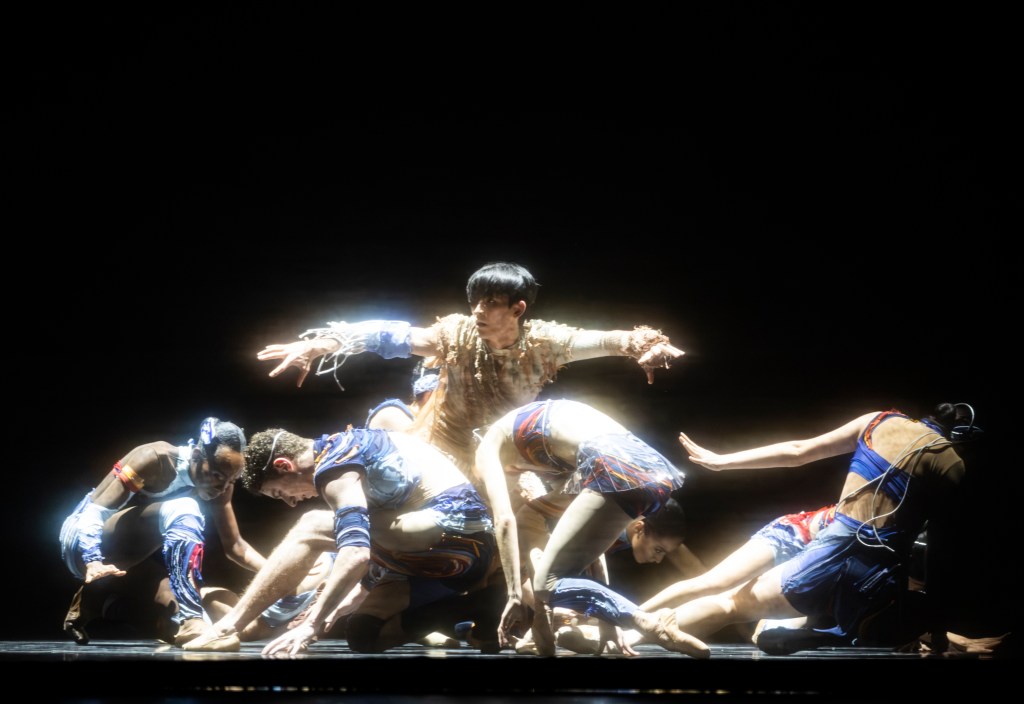

The ballet pits two protagonists (performed on Friday night by soloist Leah Terada and corps de ballet member Connor Horton) against a group of dancers called The System. The design elements establish a dichotomy between the human and the digital worlds; the protagonists wear organic and flowing sand-colored (I think) costumes and move smoothly and rhythmically across a blank stage to string music, whereas The System dancers travel in grid patterns, dance in robotic and elegantly spastic ways to updated ‘80s video game music, and wear costumes that look like chewed-up space suits.

The protagonists’ world is stark. The System’s world is bright, colorful, seductive. After setting up this contrast, Morgan and D’Ariano’s ballet asks: “Okay, what would happen if your best friend-lover-confidante fell into a video game called AfterTime and maybe got stuck in there forever?”

On the way to answering this question, Morgan and D’Ariano seem to tap movement vocabularies familiar to PNB audiences—and, of course, familiar to themselves as PNB dancers. At one point, The System dancers form an organic mass reminiscent of Crystal Pite’s The Seasons’ Canon. At the ballet’s heart-wrenching climax, the separated protagonists attempt to connect across the digital scrim in a dynamic duet inflected with the language of martial arts and classical ballet, reminiscent of moments from Price Suddarth’s Dawn Patrol. In the protagonists’ early entanglements, I saw reference to Alejandro Cerrudo’s gyroscopic choreography. And I even saw a little Giselle in the way The System attempts to dance the protagonist to death.

Though I won’t reveal the fate of the protagonists here, these are the fragments the AfterTime choreographers shore against the ruin of our contemporary, LLM robot life, where the “content” production methods are similar — we, like the LLM robots, use old art to create new art — but where a very important difference lies in the intentions of the entity behind the curtain. I think of something the late David Foster Wallace once said in an interview with a real person: “It’s gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by people who do not love us but want our money. Which is all right. In low doses, right? But if that’s the basic main staple of your diet, you’re gonna die. In a meaningful way, you’re going to die.”

As for the standout performances — the whole PNB crew killed it, with Terada very much in her element, which was good to see after an injury. Horton matched her vim and vigor and expressive capacities, which was especially impressive given that he filled in that night. And newly promoted soloist Ashton Edwards thrilled in a duet where they leapt around their partner like loosed lightning.

Despite all this noodling, I feel like I need to watch this ballet five or seven more times, and hopefully I’ll have the opportunity to.

The program then turns to Dani Rowe’s The Window, delving deeper into themes of connected disconnectedness. PNB audiences first saw this incredible work in 2023, and I hope it’s fast becoming local canon. The ballet features three characters: The Woman and The Man, who live out a little romantic life in an apartment, and The Watcher, who lives vicariously through The Woman from an apartment across the way.

Corps de ballet dancer Melisa Guilliams and principal dancer Elizabeth Murphy reprised their roles as The Watcher and the Woman, respectively, and if any other dancers have performed those roles then I don’t want to hear about it. Guilliams and Murphy are made to play these parts. Despite their difference in age and experience, the two move so similarly—soft steel, athletic elegance. Their twinning styles compound the ballet’s tragedy; suggesting that they share not only a loss in the death of The Man (played on Friday by D’Ariano, who turned in a stellar performance as a princely boyfriend, executing effortless lifts and extensions) but also the loss of what could have been a fruitful friendship.

After two Very Deep ballets, Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room hits the sensorium like a bright red firetruck. The scene looks like a Jane Fonda exercise video set in some fabulous prison. An extremely capable PNB ensemble stands onstage in black-and-white pin stripe jumpers. (Over the course of the ballet, they’ll start losing articles of clothing, revealing more skin and pops of red.) A racing score from Philip Glass starts up and does not stop. Neither do the dancers. The whole thing feels like watching a ballet at 1.5 speed, with twelve dovetailing mini-acts replete with steps from the worlds of jazz and swing. Dancers never keep a partner for long, and they all look like they’re having as much fun as anybody could possibly have on a treadmill.

In the context of this program, In the Upper Room provides the antidote to all the darkness and alienation—light, rhythm, movement, music, sharing space and sweat with people in real life! And of course, a smoke machine turned on full blast.